Unraveling The Mystery: How Many Books Were Removed From The Bible?

Detail Author:

- Name : Osborne Collins

- Username : mabel.west

- Email : maci60@yahoo.com

- Birthdate : 1998-08-09

- Address : 2165 Feeney Via Apt. 859 Stokesview, OK 91823-3786

- Phone : +1-445-622-7367

- Company : Miller Inc

- Job : Utility Meter Reader

- Bio : Magni facere minus velit magni ipsam dolores molestiae. A sint minima amet sed dolorem. Sequi enim dolores dolores eos vero distinctio.

Socials

facebook:

- url : https://facebook.com/janis.dicki

- username : janis.dicki

- bio : Reprehenderit repellendus odio ea culpa aperiam sint quis.

- followers : 3067

- following : 2353

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/dicki2014

- username : dicki2014

- bio : Sed qui maxime hic debitis quis. Maxime officiis vitae esse et nobis consequatur quia qui. Hic similique assumenda alias ratione eligendi.

- followers : 897

- following : 1729

instagram:

- url : https://instagram.com/dicki1994

- username : dicki1994

- bio : Et porro possimus ullam qui est ipsam nesciunt. Sunt voluptas eum non sed minima consequatur iusto.

- followers : 2200

- following : 997

Have you ever stopped to think about the Bible’s journey through time, and how its collection of writings came to be what it is today? It is, you know, a pretty big question for many people curious about sacred texts and their history. For a lot of folks, the idea that books might have been taken out of the Bible can be a bit surprising, or even a little unsettling. This topic, you see, often sparks lively conversations and, really, some deep reflection about faith, tradition, and what makes a text truly sacred. We are going to explore this intriguing subject, looking at how various versions of the Bible came together and what happened to certain writings along the way, drawing directly from the details we have.

The story of the Bible’s formation is not a simple one, it's almost like a tapestry woven over many centuries. Different communities, as a matter of fact, held different collections of writings in high regard. What one group considered essential, another might have viewed as helpful but not quite on the same level of authority. This difference in perspective, you know, is a key part of why the question of "removed books" even comes up. It is not always a matter of outright deletion, but sometimes a shift in how certain writings were valued or included in particular compilations.

So, we'll try to get to the bottom of this, looking at the historical moments and the different groups that played a part in shaping the Bible as we know it. We will explore the various traditions and the reasons behind their choices, offering some clarity on a topic that, frankly, can seem a bit confusing at first glance. It is a story with many layers, and we will try to peel back each one, you know, to see what is underneath.

Table of Contents

- Understanding What a Bible "Book" Is

- The Deuterocanonical Books and Their Place

- Martin Luther and His Challenges to the New Testament

- Key Councils That Shaped the Canon

- Different Bibles, Different Books

- The Hebrew Origin and Masoretic Tradition

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding What a Bible "Book" Is

To start, it is pretty helpful to grasp what we mean when we talk about a "book" within the Bible. A book in the Bible, to my understanding, is one of the many named divisions in the Old and New Testaments. These are, basically, individual writings or collections of writings that have been grouped together. So, when people ask about books being removed, they are wondering about these distinct sections. It is not, say, about individual verses, but rather whole literary pieces that were once considered part of a larger compilation, or at least discussed for inclusion, and then later found in different versions of the Bible.

This idea of a "book" is pretty important because it helps us understand the discussions and decisions that happened over centuries. Early Bible compilations, for example, did not always look exactly the same. The question of how many books were included in these early Bible compilations, and then later removed, is a significant part of the story. You know, these compilations were not just put together overnight; they were the result of a long process of discernment and acceptance by various religious communities. What made it into one collection might not have made it into another, which is a bit of what causes all the questions today.

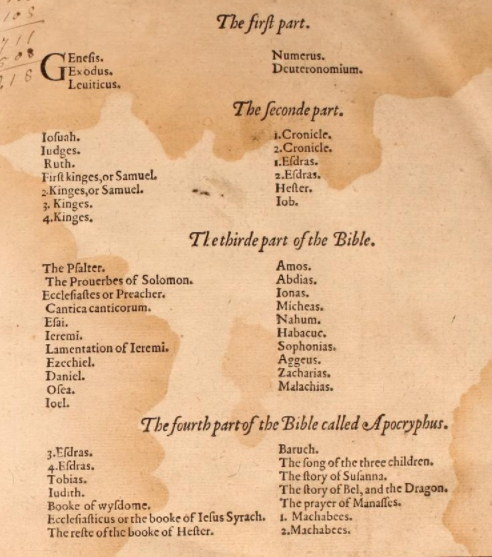

The Deuterocanonical Books and Their Place

A big part of the discussion about books being removed centers around what are often called the Deuterocanonical books. These writings, for instance, were included in the Septuagint, which is an ancient Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. However, they were not included in the Hebrew Bible, which is the collection of sacred texts used by Jewish people. This difference, you know, is a pretty important distinction that has had lasting effects on Christian traditions. The Septuagint, it is worth noting, was widely used by early Christians, so these books were quite familiar to them.

The term "deuterocanonical" itself, in a way, means "second canon," suggesting that their status was debated or affirmed later than the books universally accepted. These books include writings like Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, and parts of Esther and Daniel. It's almost like they sit in a unique spot between what everyone agrees on and what some traditions consider valuable but not quite canonical. Their inclusion or exclusion really depends on which version of the Bible you are looking at, which can be a bit confusing for someone just learning about it.

Catholic Versus Protestant Views

When we talk about the Deuterocanonical books, a pretty clear difference emerges between Catholic and Protestant Bibles. These books, you see, are mostly included in the Catholic Old Testament. For Catholics, they are considered canonical and are part of their official Scripture. This inclusion goes back a long way, to the traditions of the early Church that used the Septuagint. However, they are not in the Protestant Old Testament. This is a significant point of divergence, and it really shapes how different Christian groups view the full scope of inspired writings.

Protestants, on the other hand, typically refer to these books as the "Apocrypha," a term that means "hidden" or "obscure." While some Protestant Bibles might include them in a separate section, often between the Old and New Testaments, they do not consider them to be part of the divinely inspired canon. Since then, it is rare to find Protestant Bibles with the Apocrypha, in the US anyway, but you might occasionally come across them. This difference in acceptance, you know, has roots in the Reformation era, when various theological debates led to a re-evaluation of which books belonged in the Christian Bible.

The King James Version and Its Changes

It is really interesting to note that the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible, which is very well-known and widely used, actually included these books at one point. They were in the KJV in 1611, the year it was first published. This means that for a time, even within a prominent Protestant translation, these writings were present. However, they were removed by Protestants (of the Calvinist variety) in the 1700s. This removal was not immediate; it was a gradual process as different Protestant groups solidified their positions on the canon. So, the idea of books being "removed" is not just an ancient historical event, but something that happened relatively recently in biblical history, especially for English-speaking readers.

The decision to take them out of the KJV was, in some respects, a reflection of a broader Protestant consensus that favored the Hebrew canon for the Old Testament. This meant that any books that did not have a clear Hebrew origin, or were not part of the Jewish Masoretic tradition, were eventually excluded from the main body of the Protestant Bible. This shift, you know, really highlights how different theological understandings can lead to different collections of sacred texts. It is not just about old scrolls, but about theological principles guiding what counts as Scripture.

Martin Luther and His Challenges to the New Testament

Beyond the Old Testament books, there were also discussions and challenges concerning certain New Testament writings, particularly during the Reformation. While researching an answer to a different question, I found that Martin Luther, a central figure in the Protestant Reformation, attempted to remove Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation from the Bible. This is, honestly, a pretty surprising piece of information for many people who think of the New Testament as completely settled from the very beginning. His reasons for doing so were, basically, theological; he had concerns about how these books aligned with his understanding of salvation through faith alone.

For example, Luther famously called the Epistle of James an "epistle of straw" because he felt it emphasized works too much, which he saw as contradicting his doctrine of justification by faith. He also had reservations about the book of Revelation, finding it difficult to interpret and not clearly teaching Christ. So, it is true that Luther tried to remove James, Jude, and Revelation from the New Testament, along with Hebrews. While his attempts did not lead to these books being permanently removed from the Protestant canon, his strong opinions certainly sparked a lot of discussion and showed that even within the New Testament, there were periods of intense scrutiny and debate about which books truly belonged. This, you know, really shows how passionate people were about getting the Bible right.

Key Councils That Shaped the Canon

The question of how many books were decided at various historical councils is a pretty important one for understanding the Bible's development. For instance, we can look at the Council of Rome in 382, the Council of Carthage in 397, and the Synod of Hippo in 393. These gatherings were significant because they played a key role in affirming a list of books that became widely accepted, especially in the Western Church. They did not, you know, create the canon out of thin air, but rather formalized lists of books that were already largely accepted and used by Christian communities.

Were exactly all 73 books of the Catholic Bible declared canon at these specific councils? Well, these councils certainly affirmed a list that closely matches the 73 books found in the Catholic Bible today. They built upon existing traditions and recognized the books that had been read in churches and considered authoritative for generations. While their decisions were highly influential, it is more like they were confirming what was already widely practiced rather than introducing entirely new books. This process, in a way, helped bring a greater sense of uniformity to the biblical collection, especially as the Church grew and spread.

Different Bibles, Different Books

It is pretty clear that not all Bibles are exactly alike in their contents. Some Bibles have all four Maccabees books, for example, while others do not. Similarly, some Bibles have Esdras and Wisdom, and yet others do not. This variation shows that there was not always a complete agreement on what books would be included across all traditions. These differences, you know, often reflect the historical and theological paths taken by various Christian communities and even Jewish traditions. It is not a matter of one Bible being "more correct" than another, but rather different communities having different collections of texts they hold sacred.

The existence of these varying collections highlights that the "Bible" is not a single, monolithic entity that appeared fully formed. Instead, it is a collection of writings whose boundaries have been understood differently by various groups throughout history. For instance, some of these books, like those in the Apocrypha, would not be translated into Syriac until the 6th century, showing how their acceptance and dissemination varied across different linguistic and cultural contexts. This kind of historical detail, you know, really helps us appreciate the complex journey of these ancient texts.

The Hebrew Origin and Masoretic Tradition

A key factor in the differing lists of Old Testament books relates to their original language and the tradition of the Masoretic Jews. The Masoretic Jews, for instance, wanted those books weeded out that did not have a clear Hebrew origin. Their tradition focused on preserving the Hebrew texts that they considered sacred. And so, the other Greek books were removed, those without Hebrew origin, particularly after the Hellenization period. This period, which followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, saw a significant spread of Greek culture and language, leading to many Jewish texts being written or translated into Greek, including the Septuagint.

The Masoretic tradition, in a way, emphasized the Hebrew texts as the authoritative source for the Old Testament. This perspective eventually influenced Protestant reformers, who largely adopted the Hebrew canon for their Old Testament. This decision meant that books found in the Septuagint but not in the Hebrew Bible were eventually excluded from Protestant Bibles. It is a pretty significant historical development that explains a lot of the differences we see today between Catholic and Protestant Bibles. This focus on Hebrew origin, you know, really shaped the final collection for many.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were books truly "removed" from the Bible, or was it a matter of different canons developing?

It is more like different canons developed over time, depending on the religious community. While some books were included in early compilations like the Septuagint, they were not part of the Hebrew Bible. Later, during the Reformation, Protestant traditions, for instance, chose to exclude books that did not have a Hebrew origin, effectively "removing" them from their specific versions of the Bible, such as the King James Version in the 1700s, where they had previously been included. So, it is a bit of both, depending on your perspective and the historical period you are looking at.

What are the Deuterocanonical books, and why are they important?

The Deuterocanonical books are a group of writings, like Tobit and Judith, that were part of the Septuagint, an ancient Greek translation of the Old Testament. They are important because they are included in the Catholic Old Testament, but not in the Protestant one. This difference, you know, shows a divergence in what different Christian traditions consider to be inspired Scripture. They offer additional historical and theological insights that are valued by some Christian communities.

Did Martin Luther really try to take books out of the New Testament?

Yes, it is true that Martin Luther attempted to remove Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation from the Bible. He had theological reasons for doing so, particularly concerning how these books aligned with his understanding of salvation by faith alone. While his efforts did not result in their permanent removal from the Protestant canon, his strong opinions sparked significant debate and show that the New Testament canon, too, was subject to scrutiny during the Reformation period. You can learn more about biblical history on our site, and link to this page for more details on canon formation.

For more detailed historical context on these ancient texts, you might find information from a reputable source like a university's religious studies department or a theological library helpful. For example, you could explore resources from the Biblical Archaeology Society, which often provides background on biblical manuscripts and their history. This kind of resource, you know, can really broaden your understanding of these fascinating topics.